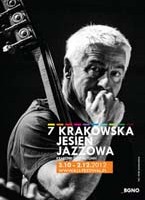

What if a bass could speak? Not by simply swinging a jazz march or bowing a lyrical cantilena, but in a voice incorporating every musical style at once? A voice free of stylistic tags and generic labels? If that were really possible, it would certainly speak in Barry Guy’s voice.

There are few musicians in the world able to soar over the turbulent eddies of improvised invention, only to show up, shortly afterwards, in a baroque orchestra and ponder the art of baroque counterpoint. For Barry Guy, this was once almost the everyday reality. For over two decades, starting back in the early 70s, Guy used his talent to bolster several famous classical musical ensembles, holding the principal bass position in The Orchestra of St John’s Smith Square, City of London Sinfonia, Monteverdi Orchestra and London Classical Players, while the years spent at Christopher Hogwood’s Academy of Ancient Music turned him into a very highly regarded interpreter of early music.

But jazz came first.

In the 60s, when the British free improvisation scene was born, he regularly played with Howard Riley – surely one of the greatest jazz individualists in Europe. And the magic of improvisation, which he developed a taste for back then when barely twenty years old, doubtlessly thrust him into the cyclone of the contemporary avant-garde. He was very visible in John Steven’s famous Spontaneous Music Ensemble or alongside icon of free expression, guitarist Derek Bailey or the great saxophone virtuoso, Evan Parker. After all, he established a musical friendship with the latter that has lasted until today, and their trio with Paul Lytton, has become one of the most famous on the European music scene.

On the one hand, a classical musician and jazzman; and on the other, an improviser and composer. This is the image of Barry Guy that has emerged after four decades following his artistic path. Yet he has already booked his place in the history of music as a pioneer linking that part of his nature that is liberated and unpredictable with the rigours of notated composition. In Guy’s case, this concept has taken on a truly spectacular form.

Back in the 70s, when European improvised music was seeking a path of its own, and Alexander von Schlippenbach, in Germany, was unveiling the improvising Globe Unity Orchestra to the world, Guy founded what is surely his most famous and, certainly at this point, his only really regularly active group, the London Jazz Composers Orchestra. Its ranks contained carefully selected soloists, and compositions were specifically written for their unique talents. All of them had already acquired considerable live performance experience, but also possessed a flair for leadership and the ability to create their own musical worlds.

A concept almost impossible to realise. A group composed of a dozen or so strong leaders positioned behind music stands, in which the individuality of each member was supposed to be reined in to suit the wider stylistic context and the dictates of a compositional plan. Is this not what Miles Davis had in mind in the 50s, when creating the Birth of the Cool Band – in the opinion of many, the first jazz ensemble to be composed of leaders – in an attempt to reconcile the combustive nature of freedom with the rules governing a collective? That’s surely the case, but Guy went further, successfully employing the accomplishments of contemporary music, a tonal language and compositional formulas that were at a far remove from jazz, thereby creating a fusion not so much of styles as musical philosophies.